Rescued by Kanban: A Real-Life Story of Using Scrum and Kanban Together

2020-11-24

I am here to tell you a story. A story of a team that was Agile at heart, tried Scrum as methodological support to materialize that agility and discovered in Kanban the best Scrum companion to face different challenges. No, it is not a story of a team doing Scrumban, but of a team choosing the right Agile method for the right set of constraints.

How did it start?

It was near the end of 2016 when I accepted to be the Scrum Master of an already built, mature, and well-established team. As a matter of fact, they were initially two teams: one backend and one frontend team. The difference between them wasn’t only visible at the kind of tasks they did, but also because they sat opposite each other, at a long table of an open office. Both teams shared the same Product Owner (PO) and with me, they were also going to share the same Scrum Master (SM). They worked almost without supervision with members that were part of the team for more than 5 years. They built a trustable flow of work that let any member (regardless of their seniority) do several deployments to production each day. On the other hand, the company was a big publisher focused on Hispanic people (mostly in the US). They had many editorial teams in different countries working with a highly customized CMS platform that also was responsible for the content distribution. The publishing business is rude and merciless. Although there are long-term plans and goals, many times you need to move quickly, adapt to different situations, deliver content to new clients, and do many, many experiments. If those experiments and changes are not done within a certain time frame, they lose their commercial value.

Everything seems perfect, don’t you think?

At the surface, yes! As I said, both teams had a very good relationship. They felt very comfortable in their workspace and had a good interaction with other teams and stakeholders. And the most important thing, they had fun and enjoyed their work! But then I started to dig in, to go deep and deep, retrospective after retrospective, and problems began to arise. And that’s normal because teams always have a place to become better versions of themselves, to reinvent or just improve how they perform each daily task. I identified three anti patterns on how both teams worked:

1. Unique conceptual user stories (US) were split (whenever was possible) into two new “user stories” (pay attention to the quotes), one for the Frontend team and the other for the Backend team. This was an issue due to the lack of a single owner responsible for each US.

Also the dependency between backend and frontend “stories” was too strong which resulted in high coupling between both backlogs. Finally, those “stories” seemed artificial and meaningless without the other counterpart, so individually they didn’t add any value to the product.

2. Some US were related to mid or long-term goals. They had to be done strategically in synchronization with commercial teams, but also, it takes more time to generate high maintainable and reliable code.

Other US were more short-term and unexpected with small validity-windows. They had to be done immediately otherwise they risked losing their business value (e.g. integration —for a month— with a potentially new distribution channel to test their effectiveness and ROI).

3. I found silos in each team. Whenever someone took a day off, every US or task related to that silo would stop until that member went back to work.

Okay, we had some problems… was it really that painful?

Yes… it was, for the team and it was hurting the business. As we said, both teams were continuously interrupted with ad hoc tasks being added to each sprint. This made mid and long-term goals look fuzzy and at times, unattainable. The team began each year with a set of clear goals to achieve, but as the year progressed, some of them were achieved while others were postponed. The worst thing was that some of these goals remained in an unknown state until a couple of months before the end of the year. When the teams realized this, they tried to finish the ones that were almost ready, sometimes without meeting the deadline or with a low-quality product. To make this visible to the team, we organized a reflection meeting where we analyzed a set of user stories to find out how and why many of them were coming and going due to quality issues and interruptions during the sprints.

The painful part shows up in the planning meetings

The team had a velocity of, let’s say 42, so in a planning meeting, they would add new stories to the backlog until they reach that number. But remember, we had those unexpected tasks falling in the middle of each sprint, so they ended the sprint with, say, 30 story points actually done. Because the team needed 12 more story points to reach the expected velocity, they added the estimated size of those unexpected tasks (an estimate made by the one who takes half the task due to the division between the backend and frontend). At the end of this mathematical challenge, they ended up with something like 40 story points… and that was taken as the speed for the next sprint. This complex process made planning long and boring. And not only that, this way of planning was completely useless because of the fact that roughly half of what was planned, most of the time got delayed to later sprints. But they continued calculating velocity because, I think, that gave a false sense of control and safety for the team and the outside.

So, what was the solution?

As a Scrum Master, I couldn’t impose a solution. I needed the team to realize by themselves that they had a problem and reach a solution. To do that, I prepared a series of retrospectives aimed to analyze previous sprints, teams’ velocities, and how they felt about the deviations they had and knowledge silos.

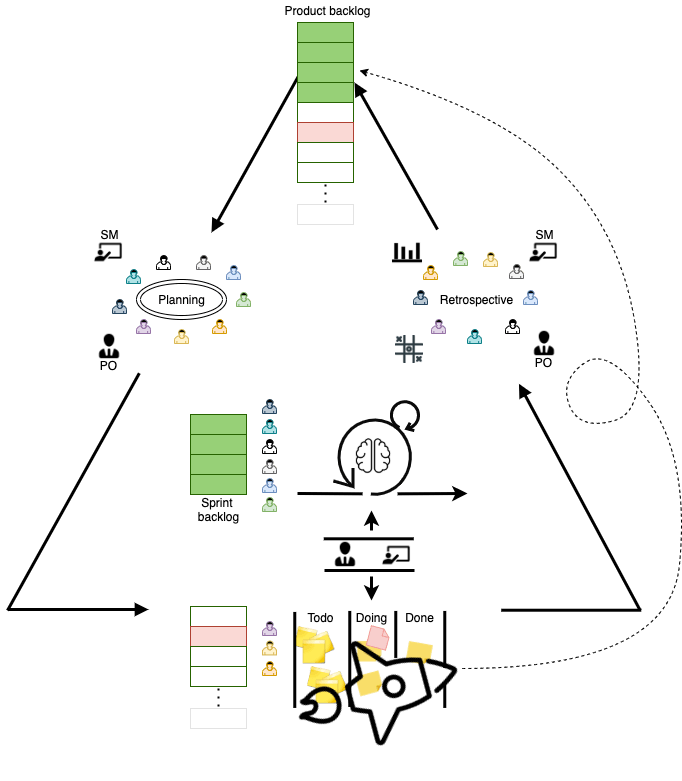

After those sessions, we, as a team, reached a solution: we were going to join both teams into one team of full-stack developers, and then that team will be split into a Scrum squad and a Kanban squad, rotating their members.

Solution break-down

Let’s break this solution of using Scrum and Kanban together piece by piece, explaining every decision and the rationale behind it. First, both squads would be composed of full-stack developers. This way knowledge silos would not exist, at least in the way it used to be, when the backend guys only did their things and the frontend theirs. Then, the Scrum squad would focus on medium to long term goals, aligned with the annual objectives of the company. This would be essential to fulfill those objectives, keeping the product competitive and aligned to the overall strategy. Using the predictivity of Scrum, based on a renewed concept of velocity, the squad could start making promises and keep them. This squad would eventually involve 80% of the team. Finally, the Kanban squad would be composed of the other 20% of the team. This squad would be free to attack non-planned tasks as soon as they arrived, without interrupting anyone. The PO (or formerly PO that now would be something like a product manager) would have the responsibility to keep the backlog prioritized, so the squad would grab tasks from there.

How (when and why) both squads rotate their members?

In one of the retrospectives, some members of the team said they like the rush, the adrenaline of being with the “fire extinguisher” chasing bugs in production and hot fixing them. Others said they like having time to test things, let ideas grow and mature in their heads, doing some proof of concepts (PoCs), researching, and then jump to code cleaner solutions. But both agreed they don’t want to be always doing the same – the first group, because it is exhausting while the second because they didn’t want to get bored. Giving these preconditions, we decided to rotate squad members. How? The team was free to choose. Initially, they kept a record of who was in Kanban, so at the end of each planning (beginning of the sprint), the Kanban squad was filled with those who had not yet been there.

How did this work for the first 3 months?

To be honest, it didn’t work wonders at first (as I expected) considering that we made a monumental change moving the foundation of an established team. The overall productivity was suboptimal, initially affected by the dissolution of the information silos. Team members with the knowledge to take specific tasks had to overcome the temptation to do it and instead, start doing pair programming with other devs or, in other cases, they had to prepare and do knowledge transfer sessions. All of that extra work reduced the time they dedicated to developing, and the productivity of the one doing the job wasn’t too impressive. The other problem was the conversion from backend or frontend developers to full-stack. To solve this, we choose the same strategy as with the previous problem, adding courses over needed technologies, internal talks, and wikis with information to share. So, sprints continued being interrupted. But this time by knowledge transfer tasks instead of non-planned tasks.

Conclusions after a year

The first thing that filled me with pride was the way the squads self-organized. For example, in some sprints, some members continued in the same squad for one sprint more because they felt it was needed, but in others, I heard some of them exclaiming: “Hey, if I keep doing this, I’ll keep all the knowledge and that’s something we don’t want”. By combining Scrum and Kanban together, the Scrum squad could work fully dedicated to main company goals and product features. In our “end of the year meeting”, we previously used to arrive with few goals achieved and many half baked —almost there— goals. Unlike other years, this time we arrived with every single goal achieved. Also, our Kanban squad was very active, significantly reducing the number of existent bugs in the backlog and improving the number of PoCs built. Some of these PoCs contributed directly to the company goals becoming important features of the main product. Indeed one of those PoCs became so big (and successful) that it was converted into a full product, giving additional and unexpected monetary incomes to the company that year. Finally, the Backend and Frontend division disappeared. Obviously, they had preferences, but we were one big team. The moral of it was higher enough to face a new one-year-long project with several challenges, risks, and pressure full of energy.

Acknowledgments

This post was written as a guest post for the Kanbanize blog, so I want say thanks to them for let me share this with you in my homepage.

Significant Revisions

Nov 24, 2020: Original publication on kanbanize.com

Nov 26, 2020: Original publication on dariomac.com